Linking Early Childhood Education Classrooms to Develop Global Identities

As soon as they are born, young children start learning about themselves and their world. As they grow, they develop a sense of their own identity and begin to recognize similarities and differences in others. This recognition grows into an understanding of belonging to one’s family and eventually expands to include recognition of their place within broader communities. One of the important roles of educators is to help children, including young children, develop a sense of identification with and awareness of those broader communities, including global ones. Global citizenship education (GCED) supports and promotes this identification, helping children to appreciate diversity, navigate differences, develop empathy and perspective, and acknowledge and understand the interconnected nature of our world.

These foundational understandings of GCED provide the basis for later development of complex ideas, including informed, ethical decision-making; global social responsibility; and collaborative, transformative actions to provide solutions that meet the challenges of our world. One way to help develop GCED foundational understandings in early childhood education (ECE) is by challenging students through interactions with peers who may look, speak, and act in unfamiliar ways and then supporting them as they make sense of those differences. This case study examines a preschool partnership between two schools, one in Belgium and one in Zambia, that facilitates such interactions, helping preschool-age children develop their identities as global citizens by learning about each other and from one another.

These foundational understandings of GCED provide the basis for later development of complex ideas, including informed, ethical decision-making; global social responsibility; and collaborative, transformative actions to provide solutions that meet the challenges of our world. One way to help develop GCED foundational understandings in early childhood education (ECE) is by challenging students through interactions with peers who may look, speak, and act in unfamiliar ways and then supporting them as they make sense of those differences. This case study examines a preschool partnership between two schools, one in Belgium and one in Zambia, that facilitates such interactions, helping preschool-age children develop their identities as global citizens by learning about each other and from one another.

VVOB – education for development runs a program called SchoolLinks1, which builds and supports partnerships between schools in Flanders (Belgium) and schools in the Global South (Africa, Central and South America, Asia). These one-on-one partnerships always revolve around educational goals and allow learners and teachers from both schools to learn not only about each other, but also with and from each other, as it brings “the world” into their classrooms.

Through the program, VVOB creates links between schools offering basic and/or secondary education, and with increasing frequency between ECE contexts. ECE teachers around the world want to collaborate with their teaching colleagues by participating in SchoolLinks. Having a school link helps to broaden the horizons of learners and educators by introducing them to the diversity of people and cultures around the world, and promoting respect for other people in their differences. It also makes global issues more tangible and offers teachers a tool for tackling stereotypes and enriching the subjects they teach with an international perspective.

While many schools have been nurturing their partnerships successfully for years now, the school link between Magnolia School in Ukkel (Belgium) and Lukanga Primary School in Kabwe (Zambia) – which also offers ECE – is a new one.

While many schools have been nurturing their partnerships successfully for years now, the school link between Magnolia School in Ukkel (Belgium) and Lukanga Primary School in Kabwe (Zambia) – which also offers ECE – is a new one.

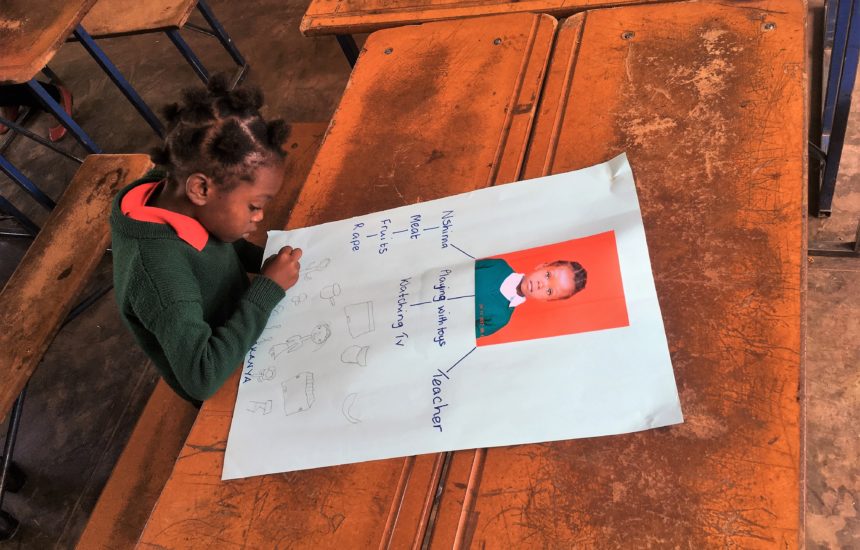

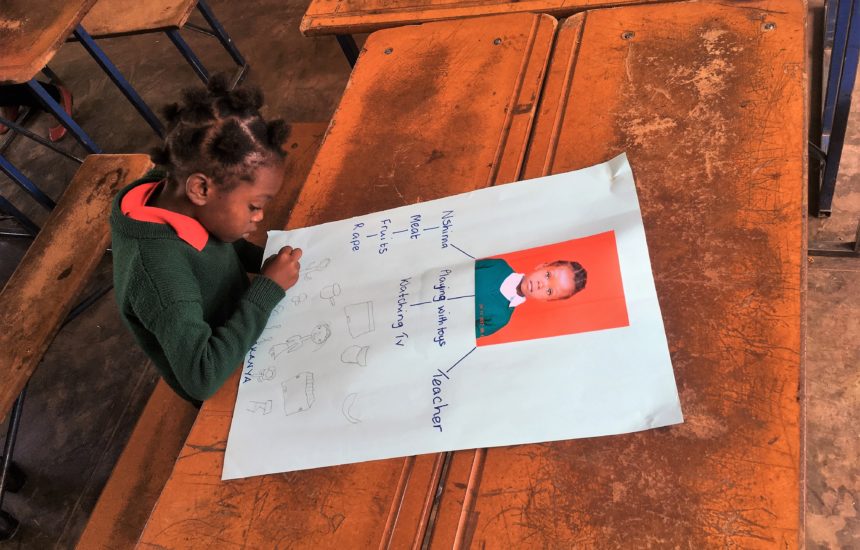

One of the first activities the teachers in Lukanga and Magnolia did with their learners, as an introduction to their school link, was making a drawing or collage about their favorite things: food, games, toys, and so on. Next, the schools exchanged those pieces of art. The teachers then had a conversation with their young learners and compared their own interests to those of their peers on the other continent. This gave the teachers an opportunity to talk about the differences, and just as much about the similarities between children worldwide. The preschoolers saw with their own eyes that no matter the distance or different context, they have more in common with their peers than what they might think at first.

Belgian preschool teachers Charlotte, Stephanie, and Sofie work at Magnolia and traveled to their partner school to meet their Zambian colleagues for the first time. In the interview below, they talk about their first impressions and future plans.

What was the biggest surprise about education [in Zambia]?

Sofie: “I thought the preschoolers would have to repeat a lot of what the teacher said, but that wasn’t the case. The preschool teachers develop a lot of their own materials with which the children can do their own thing. They make those materials with stuff they find at home, in the streets, or in nature . . . they’re very creative! Despite limited resources and infrastructure, they’re very motivated to move forward with their learners. In Belgium, we tend to buy learning materials that may be too complicated. This visit made us realize we can also have an impact with little resources.”

Stephanie: “I also noticed how they focus on their learners’ ability to be independent. They teach them how to garden and cook, very concrete skills they’ll need in their day-to-day lives. The ‘special needs’ classroom is another great project. Learners with difficulties or disabilities have an equal opportunity to learn. Multiple teachers are in the classroom to support every child as well as possible.”

You teach very young children. How does a school link contribute to their development?

Charlotte: “Our youngest are introduced to ‘the big world out there’ for the first time. We let them discover the possibilities, we teach them how to communicate. The preschoolers in both schools learn from each other through a song, a game, a video message. In the third year of preschool, the school link takes a philosophical turn. We stimulate their critical thinking and open attitude. A school link between preschoolers can be the basis for their global citizenship.”

The visit had two goals: getting to know each other and developing an action plan that will be the framework of your partnership. How did that go?

Sofie: “Relatively easy! Our first brainstorm led to a long list of possible themes to work on together. Eventually, we chose three: culture (typical games, dress, ceremonies, music); plants, animals, and nature; and talents and skills. Then we thought about how we could work on these themes at the level of the children, the teachers, and the broader school environment.

Stephanie: “Decisions about the budget were tougher to make. In Belgium, we’ll easily get our hands on the necessary materials to do the activities. That’s not the case for Zambia. Our colleagues still need to buy [items] for the project, [including] an internet bundle to be able to communicate.”

Looking forward, what do you hope to learn from the school link, both as a teacher and a Belgian?

Charlotte: “I hope the school link takes on a life of its own in our school, with teachers and parents fully involved, and that our small ideas evolve into something grand. We can use the school link as an inspirational tool to introduce the world to our learners, and to invite them to think with an open mind. On a more personal level, I hope this new way of working together will teach me how to communicate better and will give me more insight into cultural diversity.”

Sofie: “I also hope that the school link takes on a life of its own in both schools, and that we can make something good of it. I want to get to know the Zambian school, its learners and teachers even better by working together on the chosen themes. We’ll constructively exchange ideas, learn from each other and be open for change and innovation.”

Stephanie: “We’re going to learn so much from them, and I want to return that favor by inspiring them with practices from our Belgian context. We’ll both be enriched with new ideas and experiences. There’s no better way to grow as a teacher.”

Interactions between schools at all levels can help teachers support students to explore topics such as tolerance, shared values, and a sense of a common humanity. Building a firm sense of these foundational understandings at a young age can support further engagement with complex ideas as students grow older and become developmentally ready.

Interactions between schools at all levels can help teachers support students to explore topics such as tolerance, shared values, and a sense of a common humanity. Building a firm sense of these foundational understandings at a young age can support further engagement with complex ideas as students grow older and become developmentally ready.

Note: